Battle of the sexes (game theory)

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

In game theory, battle of the sexes (BoS), also called Bach or Stravinsky,[1] is a two-player coordination game. Imagine a couple that agreed to meet this evening, but cannot recall if they will be attending the opera or a football match. The husband would most of all like to go to the football game. The wife would like to go to the opera. Both would prefer to go to the same place rather than different ones. If they cannot communicate, where should they go?

The payoff matrix labeled "Battle of the Sexes (1)" is an example of Battle of the Sexes, where the wife chooses a row and the husband chooses a column. In each cell, the first number represents the payoff to the wife and the second number represents the payoff to the husband.

This representation does not account for the additional harm that might come from not only going to different locations, but going to the wrong one as well (e.g. he goes to the opera while she goes to the football game, satisfying neither). In order to account for this, the game is sometimes represented as in "Battle of the Sexes (2)".

Contents |

Equilibrium analysis

This game has two pure strategy Nash equilibria, one where both go to the opera and another where both go to the football game. For the first game, there is also a Nash equilibrium in mixed strategies, where the players go to their preferred event more often than the other. For the payoffs listed above, each player attends their preferred event with probability 3/5.

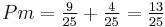

This presents an interesting case for game theory since each of the Nash equilibria is deficient in some way. The two pure strategy Nash equilibria are unfair; one player consistently does better than the other. The mixed strategy Nash equilibrium (when it exists) is inefficient. The players will miscoordinate with probability 13/25, leaving each player with an expected return of 6/25 (less than the return one would receive from constantly going to one's less favored event).

One possible resolution of the difficulty involves the use of a correlated equilibrium. In its simplest form, if the players of the game have access to a commonly observed randomizing device, then they might decide to correlate their strategies in the game based on the outcome of the device. For example, if the couple could flip a coin before choosing their strategies, they might agree to correlate their strategies based on the coin flip by, say, choosing football in the event of heads and opera in the event of tails. Notice that once the results of the coin flip are revealed neither the husband nor wife have any incentives to alter their proposed actions – that would result in miscoordination and a lower payoff than simply adhering to the agreed upon strategies. The result is that perfect coordination is always achieved and, prior to the coin flip, the expected payoffs for the players are exactly equal.

Working out the above

Let us calculate the four probabilities for the actions of the individuals (Man and Woman), which depend on their expectations of the behaviour of the other, and the relative payoff from each action.

The Man either goes to the Football or the Opera (and not both or neither), and likewise the Woman.

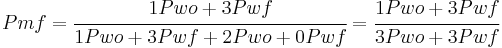

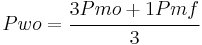

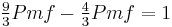

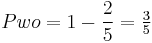

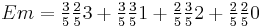

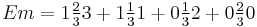

The Probability that the man goes to the football game,  , equals the payoff if he does (whether or not the woman does), divided by the same payoff plus the payoff if he goes to the opera instead:

, equals the payoff if he does (whether or not the woman does), divided by the same payoff plus the payoff if he goes to the opera instead:

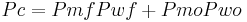

We know that she either goes to one or the other, so  , so:

, so:

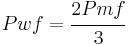

Similarly:

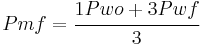

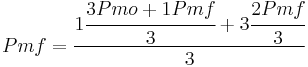

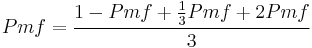

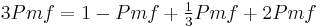

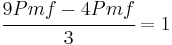

This forms a set of simultaneous equations. We can solve these, starting with  for example, by substituting in the equations above:

for example, by substituting in the equations above:

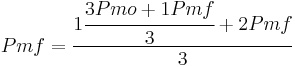

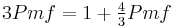

Remembering that  , we can make this an equation where the only unknown is

, we can make this an equation where the only unknown is  :

:

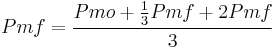

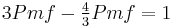

And then rearrange so that  is only on one side:

is only on one side:

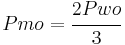

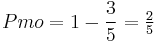

Knowing that  , we deduce:

, we deduce:

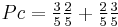

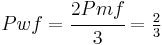

Then we can calculate the probability of coordination  (that M and W do the same thing, independently), as:

(that M and W do the same thing, independently), as:

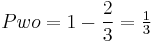

And the probability of miscoordination  (that M and W do different things, independently):

(that M and W do different things, independently):

And just to check our probability working:

So the probability of miscoordination is  as stated above.

as stated above.

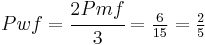

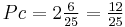

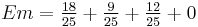

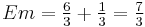

The expected payoff E for each individual ( and

and  ) is the probability of each event multiplied by the payoff if it happens. For example, the Probability that the man goes to football and the Woman goes to football multiplied by the Expected payoff to the man if that happens (

) is the probability of each event multiplied by the payoff if it happens. For example, the Probability that the man goes to football and the Woman goes to football multiplied by the Expected payoff to the man if that happens ( ):

):

Which is not the same as the  stated above!

stated above!

For comparison, let us assume that the man always goes to football and the woman, knowing this, chooses what to do based on revised probabilities and expected values to her:

This is symmetric for  if the woman always goes to the opera and the man chooses randomly with probabilities based on the expected outcome, due to the symmetry in the value table. But if both players always do the same thing (both have simple strategies), the payoff is just 1 for both, from the table above.

if the woman always goes to the opera and the man chooses randomly with probabilities based on the expected outcome, due to the symmetry in the value table. But if both players always do the same thing (both have simple strategies), the payoff is just 1 for both, from the table above.

Burning money

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

Interesting strategic changes can take place in this game if one allows one player the option of "burning money" – that is, allowing that player to destroy some of her utility. Consider the version of Battle of the Sexes pictured here (called Unburned). Before making the decision the row player can, in view of the column player, choose to set fire to 2 points making the game Burned pictured to the right. This results in a game with four strategies for each player. The row player can choose to burn or not burn the money and also choose to play Opera or Football. The column player observes whether or not the row player burns and then chooses either to play Opera or Football.

If one iteratively deletes weakly dominated strategies then one arrives at a unique solution where the row player does not burn the money and plays Opera and where the column player plays Opera. The odd thing about this result is that by simply having the opportunity to burn money (but not actually using it), the row player is able to secure her favored equilibrium. The reasoning that results in this conclusion is known as forward induction and is somewhat controversial. For a detailed explanation, see [1] p8 Section 4.5.

References

- Luce, R.D. and Raiffa, H. (1957) Games and Decisions: An Introduction and Critical Survey, Wiley & Sons. (see Chapter 5, section 3).

- Fudenberg, D. and Tirole, J. (1991) Game theory, MIT Press. (see Chapter 1, section 2.4)

- ^ Osborne, Rubinstein (1994). A course in game theory. The MIT Press.

External links

- GameTheory.net

- Cooperative Solution with Nash Function by Elmer G. Wiens